Math in… Quantum Computing

In December, Google announced Willow, a quantum chip that managed to run a computation in five minutes that would take today’s best non-quantum supercomputers 10²⁵ = 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 years. (The universe is currently estimated to be only 13,700,000,000 years old.)

The chip’s architecture features 105 qubits, the basic units of quantum information, and demonstrated that more qubits can be used to help with error correction.

This February, Microsoft announced their Majorana 1 chip, a new approach to quantum computing based on long-conjectured but recently-discovered Majorana fermions (subatomic particles).

The Majorana 1 currently has 8 qubits, but Microsoft’s goal is scale this to 1,000,000 qubits in a single chip, and their new materials give them confidence that this will be possible.

Why are these chips such a big deal?

Scientists have been flirting with the concept of quantum computing since the 1960s. In 1992, David Deutsch and Richard Jozsa devised a problem that a quantum computer could solve quickly that a conventional computer could not.

More quantum algorithms were quickly published, culminating in a result published by Peter Shor in 1994.

Shor’s algorithm tackles efficiently computing discrete logarithms and integer factorizations. These computations are so classically tricky that cryptosystems like RSA and elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) rely on the fact that, for large numbers, nobody knows how to perform them in reasonable amounts of time and conventional computers aren’t much help.

In 2001, IBM used a variant of Shor’s algorithm to factor 15 using 7 qubits. This might seem a little underwhelming, since we know the factorization of 15, but the number of qubits limits the size of the integer and determines the amount of error that creep into the calculation. The number 35 proved too big to factor without errors for IBM’s 20-qubit system in 2019, but Google and Microsoft’s recent work is a step toward making quantum factoring of larger integers possible and ending the modern era of cryptography.

The power of quantum computers comes from the way they store and process information.

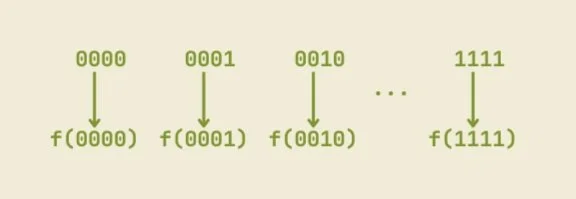

When a conventional computer performs the same calculation on the numbers 0 through 15, it performs it on each of the sixteen values, for sixteen calculations total.

It can do these calculations one after another, taking more time, or simultaneously, requiring more CPU cores.

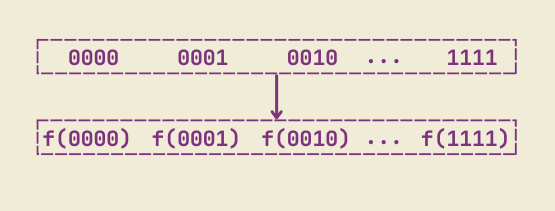

A quantum computer instead performs the operation once on a superposition of 0 through 15 and gets a superposition of answers.

If we want to exponentially increase the number of values in the superposition, we can use a few more qubits instead of exponentially increasing the computing time or number of CPU cores. This makes it possible to perform a mind-boggling number of calculations, all at the same time.

The rub is that, when you try to read this superposition of answers, you end up getting only one of those answers, and it might not be the one you’re interested in. For a quantum computer’s calculation to be useful, there needs to be a way to convert a superposition into a meaningful output and not a seemingly random one.

Shor’s trick was to construct a superposition related to a useful repeating sequence of numbers and use a quantum Fourier transform to find the period of the sequence. Since it was actually this period that was crucial to his calculations, it didn’t matter if he had access to the full sequence.

Three decades later, mathematicians and scientists are still hunting for creative ways to wrangle quantum superpositions into useful outputs so that we have a library of quantum algorithms when the technology is ready.

Why are mathematicians interested in quantum computers?