Math in… Molecules

The atoms and unpaired electrons in a molecule help inform its geometry, which in turn governs much of its chemical properties.

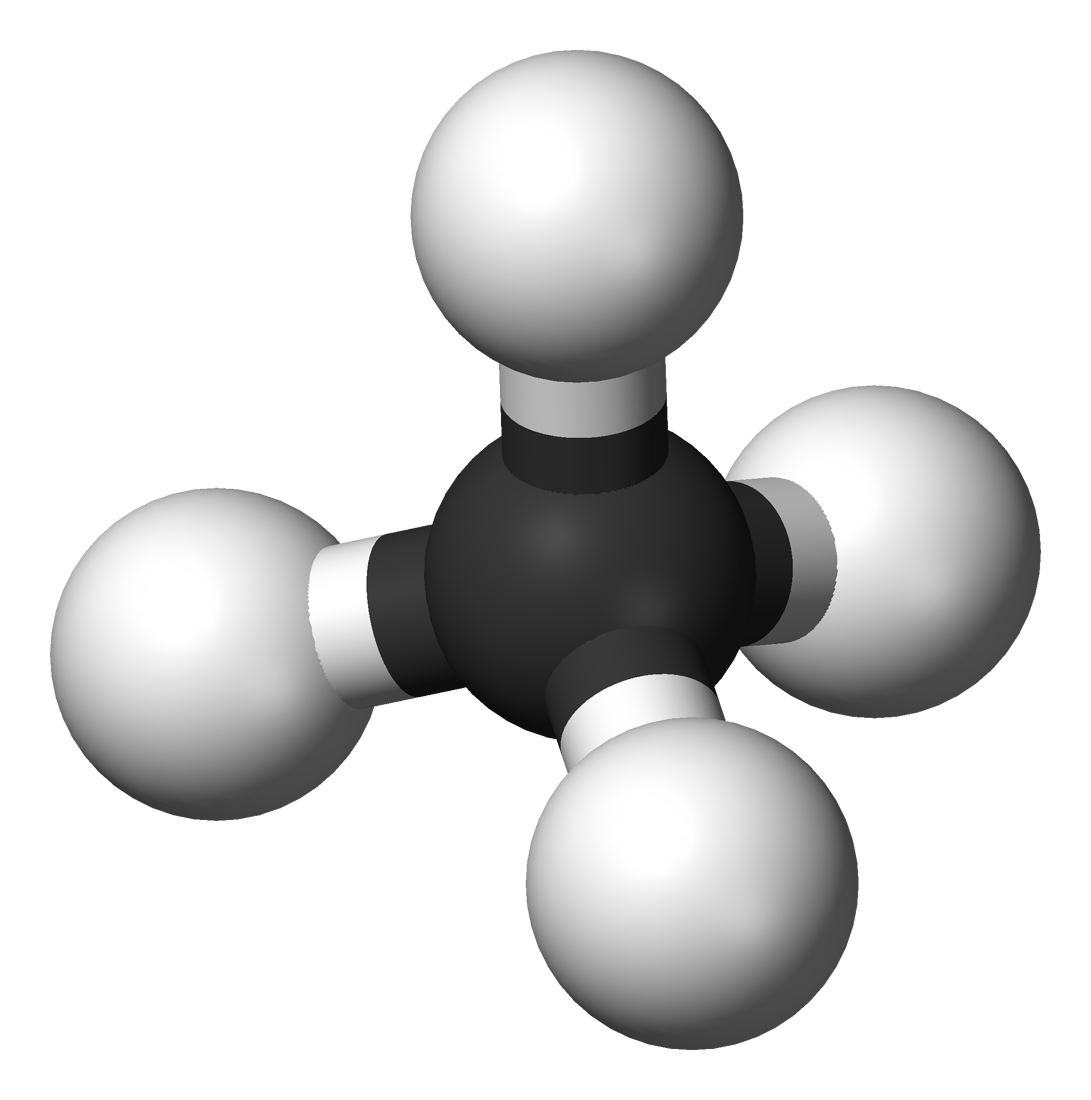

A methane molecule (CH₄) is made up of one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms. Because the hydrogens repel each other, they seek out positions around the carbon atom that are mutually farthest from one another. The result is that the hydrogen atoms organize themselves at the vertices of a regular tetrahedron, forming 109.5° angles.

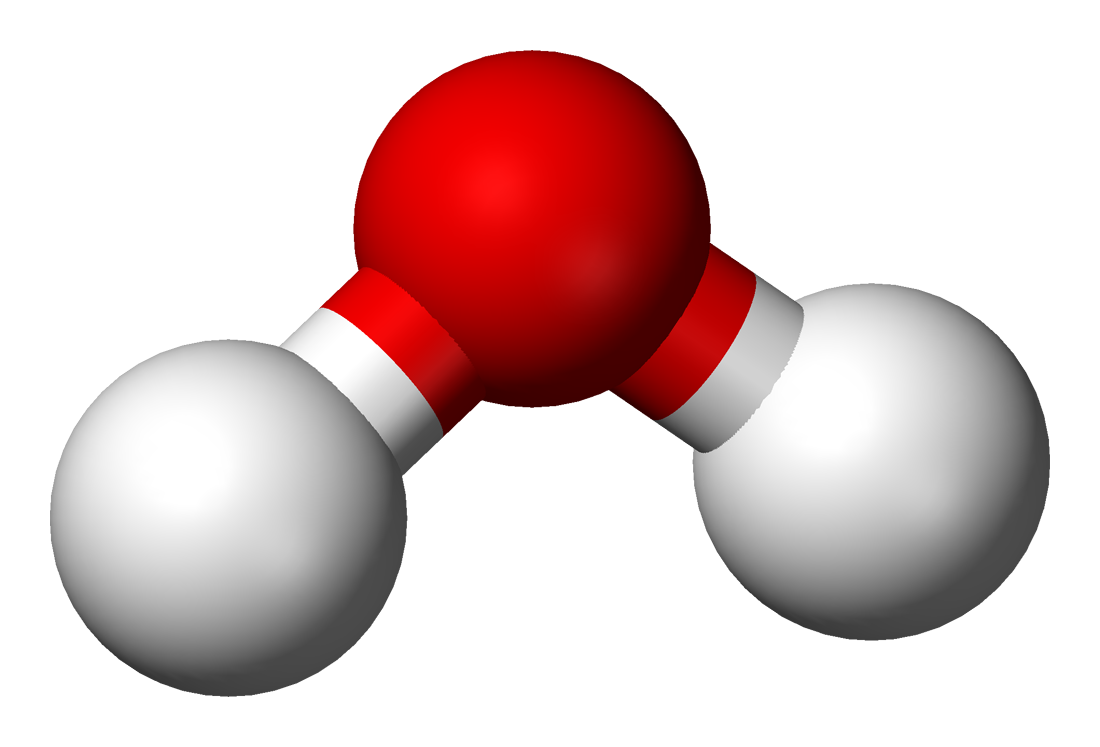

While a water molecule (H₂O) doesn’t have four hydrogen atoms, the two hydrogen atoms still form an angle. This is because the two unpaired electrons also repel each other and the hydrogen atoms, so the two unpaired electrons and two hydrogen atoms in water position themselves similarly to the four hydrogen atoms in methane.

Unpaired electrons repel each other more strongly than hydrogen atoms, so the four positions are not quite the vertices of a regular tetrahedron. The hydrogen atoms instead form a 104.5° angle.

Because the oxygen atom’s unpaired electrons are more negatively charged than the hydrogen atoms, water is polar, having a positive end and negative end.

This polarity makes water molecules attract one another and makes it so other polar molecules, like salt and sugar, dissolve well in water.

Methane, on the other hand, is symmetric in a way that makes it nonpolar.

Methane molecules can attract each other, but via temporary dipoles formed through motion of electrons.

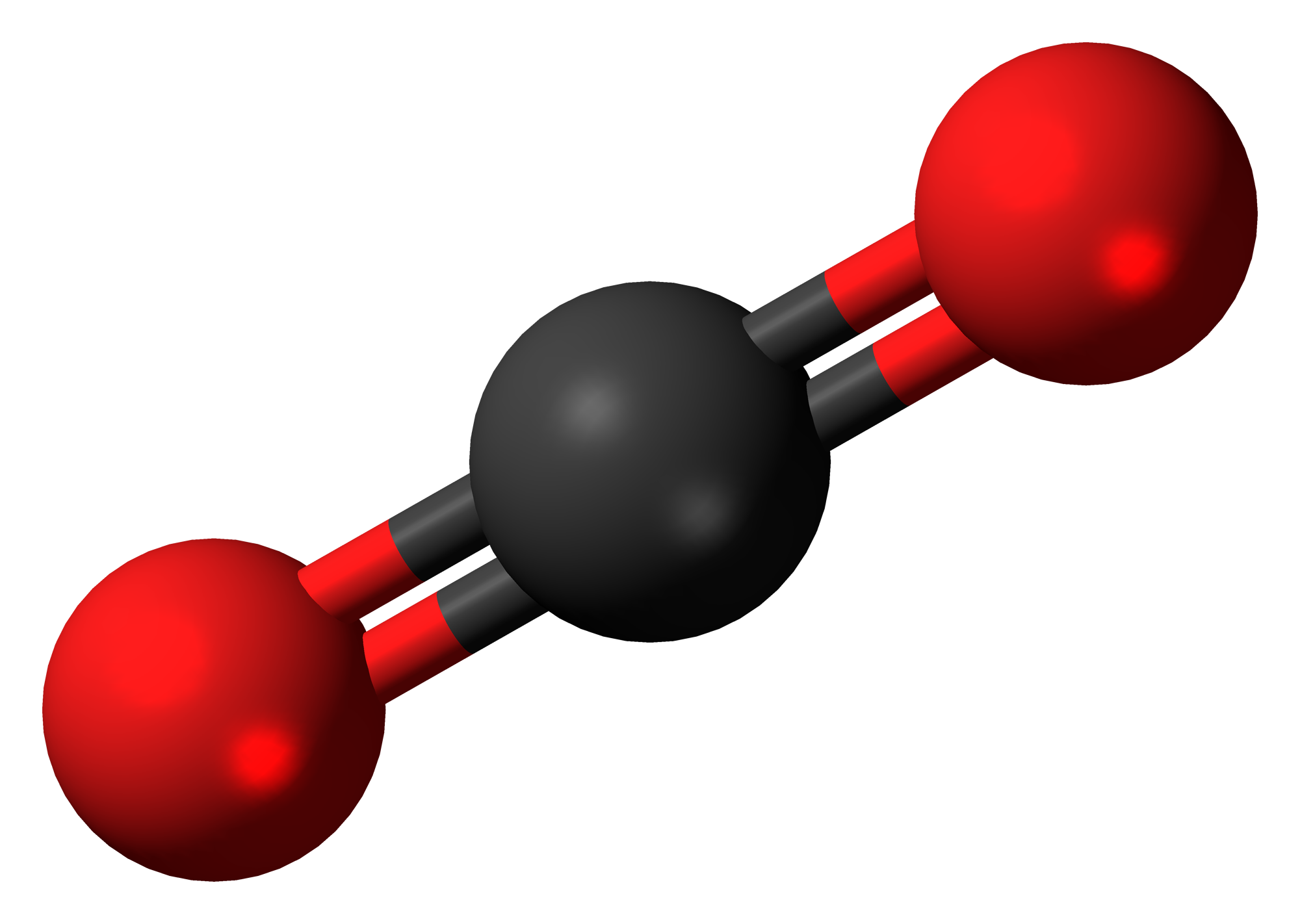

There are no unpaired electrons in a carbon dioxide molecule (CO₂), so with only two oxygen atoms to arrange around the carbon atom, the molecule is linear.

Due to its reflectional and rotational symmetry along this axis, it is nonpolar.

While the symmetry of molecules can help predict properties like polarity, scientists have found other reasons the sort molecules by symmetry type. Using group theory, a field of math that provides algebraic tools for investigating symmetry, scientists have used symmetries to study molecular vibrations, orbital arrangements, quantum numbers, and other phenomena.

While scientists use mathematical tools to help investigate their questions about the natural world, their questions also spark interesting mathematical problems. The positions of atoms and electrons around another atom led mathematicians to the Thomson problem:

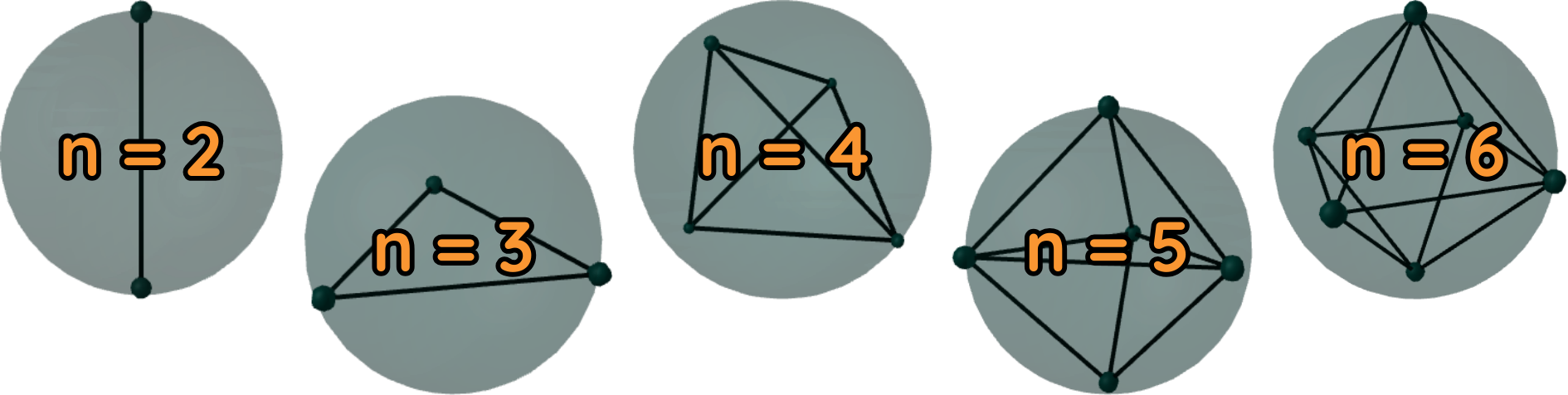

Given n electrons on a spherical shell, all repelling each other according to Coulomb’s law, where can they position themselves to minimize energy?

Let’s take a look at their shapes:

When n = 4, the solution is indeed the vertices of a regular tetrahedron.

For n = 6, the solution is the vertices of a regular octahedron.

You might suspect a solution for n = 8 forms the vertices of a cube, but it turns out the vertices of a square antiprism achieve lower energy. It’s still unknown whether the best arrangements found for n = 7 or n = 8 are actually the best possible!