Math in… Probabilistic Fallacies

If you roll five six-sided dice and each comes up showing a six, how likely are you to roll a six with your next roll?

Sixes seem hot! Perhaps there is a better than average chance that a six comes up next?

Or maybe the dice need to “make up” for the fact that too many sixes have been rolled. Could rolling a six now be less likely than usual?

Both of these stories might feel compelling, despite having opposite conclusions — but is either correct?

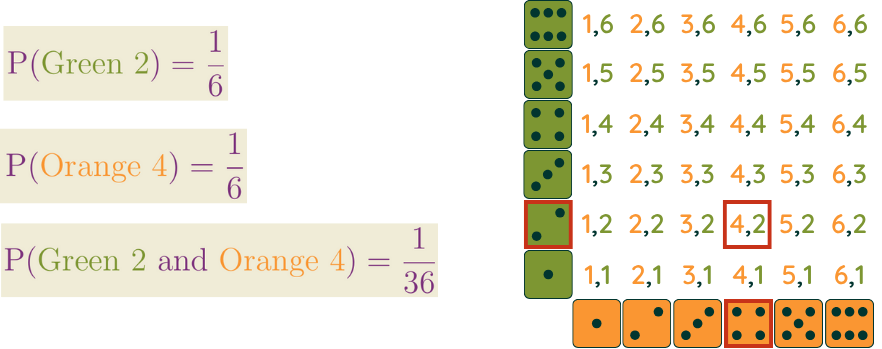

A fair six-sided die has a ⅙ probability of rolling each value and the outcomes of distinct rolls are independent.

Two events A and B are independent if their probabilities satisfy

P(A∩B) = P(A) ∙ P(B)

where A∩B is the event that A and B both occur. It’s technical, but events being independent in this sense means that they don’t influence each other, as you might hope it would.

With fair dice, the probability of rolling a six next is ⅙, regardless of previous rolls. Why might we think they would be more or less likely?

Our tendency to look at a string of independent outcomes and predict more of the same is called the hot hand fallacy, named after athletic “hot hand” streaks of above-average performance.

While things like psychology can affect consistency of athletic performance, statisticians looking for evidence of hot hands in sports have found that hot streak lengths have distributions you would expect from independent events.

It’s not hard to see why seeing an outcome over and over might make people suspect the odds have shifted to favor it, even if they know better.

Our tendency to look at a string of independent events and predict trends to swing the other way is known as the gambler’s fallacy.

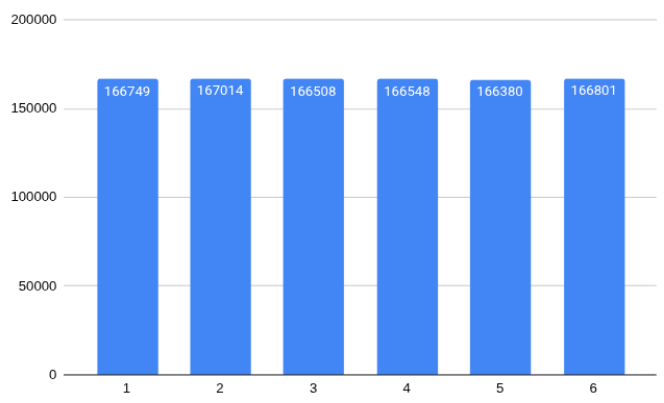

The law of large numbers says that after a huge number of dice rolls, we expect about ⅙ of them to be ones, ⅙ to be twos, and so on, as in this simulation of one million die rolls:

The law of large numbers correctly predicts the bars should have about the same heights. (You might not have noticed there were 634 more twos than fives!) The gambler’s fallacy might look at this data and incorrectly make predictions based on a deficit of 634 fives that “needs” to be cleared.

While we’d certainly see fives as we continue to roll more and more, there’s no real reason to expect a five on the next roll or that the number of fives we see will at some point exactly equal the number of twos. The law of large numbers only predicts that the ratio of twos to fives will tend to 1.

It can be enticing to think in terms of these fallacies when they give us hope, though, even if we know the logic isn’t so sound!

Can you think of a time you fell for the hot hand fallacy?

What about the gambler’s fallacy?