Math in… Video & Audio Sampling

Have you ever seen a video of a helicopter that appears to float while its propellor stands still? Or a car that seems to be moving forward, but its wheels are spinning the other way?

It's all because of how videos work - by showing still pictures really quickly so it looks like things are moving smoothly.

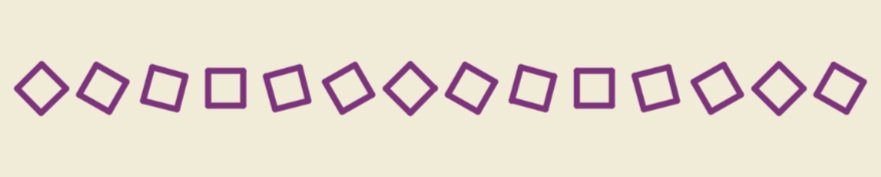

Reading left-to-right, do the squares rotate clockwise or counterclockwise?

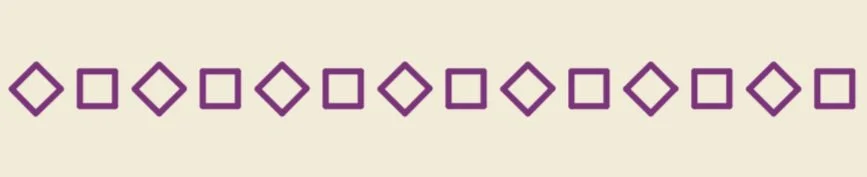

Assuming the above pattern of squares repeats indefinitely, what if you are shown only every 15th square?

Every 9th square?

Every 18th square?

When two different signals are sampled at the same rate and produce the same sequence of snapshots, it's called "temporal aliasing." The snapshots below could've been of a square quickly spinning clockwise or slowly spinning counterclockwise, but your brain instinctively fills in the low-frequency solution.

Many cameras that record video shoot at 24 frames per second. This can cause problems when things are spinning quickly. The same goes for recording music, too -- if we don't record sound at a high enough rate, the music can sound “off" in a hard-to-describe way.

According to the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem, to avoid these problems, we need to sample things at a rate that's more than twice the highest frequency we want to capture. Since humans can't hear sounds above around 20,000 hertz, or cycles per second, the sampling rate for recording audio should be more than 40,000 samples per second.

That's why a lot of sound technology uses a sampling rate of 44,100 samples per second - to make sure we capture all the important details.

What kind of music do you like to listen to?